Devonshire House is such a hidden secret in London’s West End that it no longer exists. Yet the legacy of the Duke of Devonshire’s London pad remains.

Words by John Rogers

From fire damage to becoming one of London’s finest mansions, to its eventual demolition and replacement by offices, the history of Devonshire House is enormously rich.

Two hundred years at the heart of London’s social life scene provides plenty of stories and an impressive cast of characters, from politicians to royalty.

So, pull up a pew as we venture down Memory Lane (or, more accurately, Piccadilly) and discover the hidden secrets of Devonshire House, one of London’s long-lost gems.

The History of Devonshire House

Ready to nerd out? Let’s take a look at the history behind this very famous house.

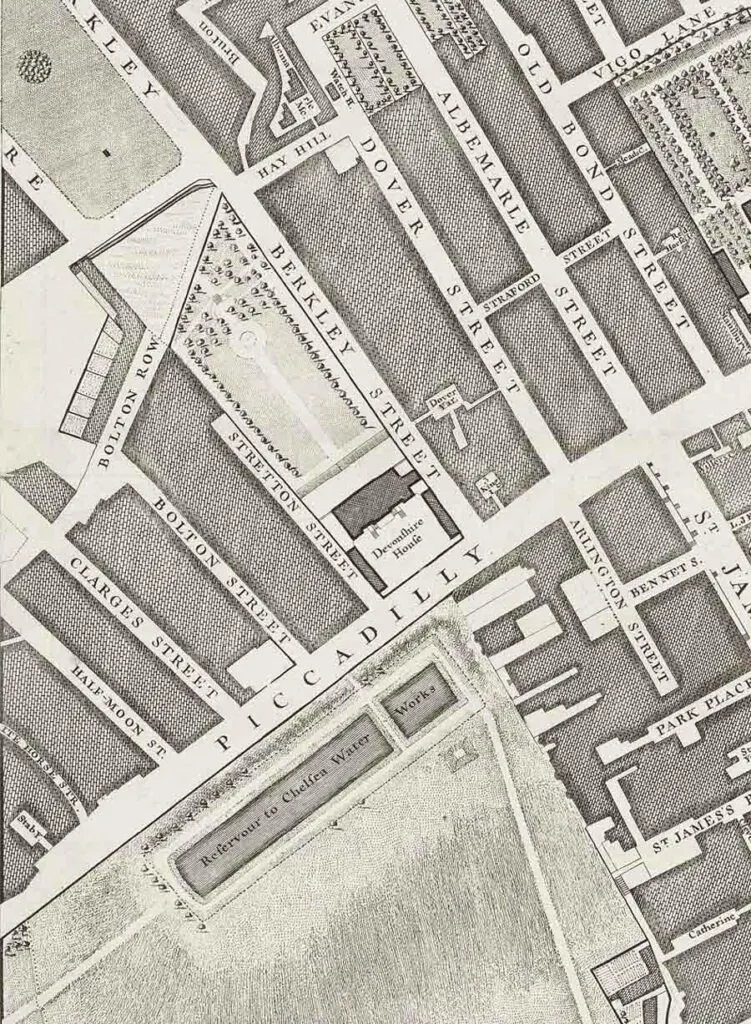

Devonshire House came into being in 1696 when William Cavendish, the 1st Duke of Devonshire, purchased Berkeley House, built between 1665 and 1673. In true Duke fashion, he changed the name in his own honour.

The house, now the site of Berkeley Square, was destroyed on 16th October 1733 by fire, despite the firefighting efforts of the Regiment of Guards and local troops led by the Prince of Wales.

The house was undergoing refurbishment at the time, and (surprise, surprise) the finger of blame was pointed squarely at careless labourers.

The Second Devonshire House

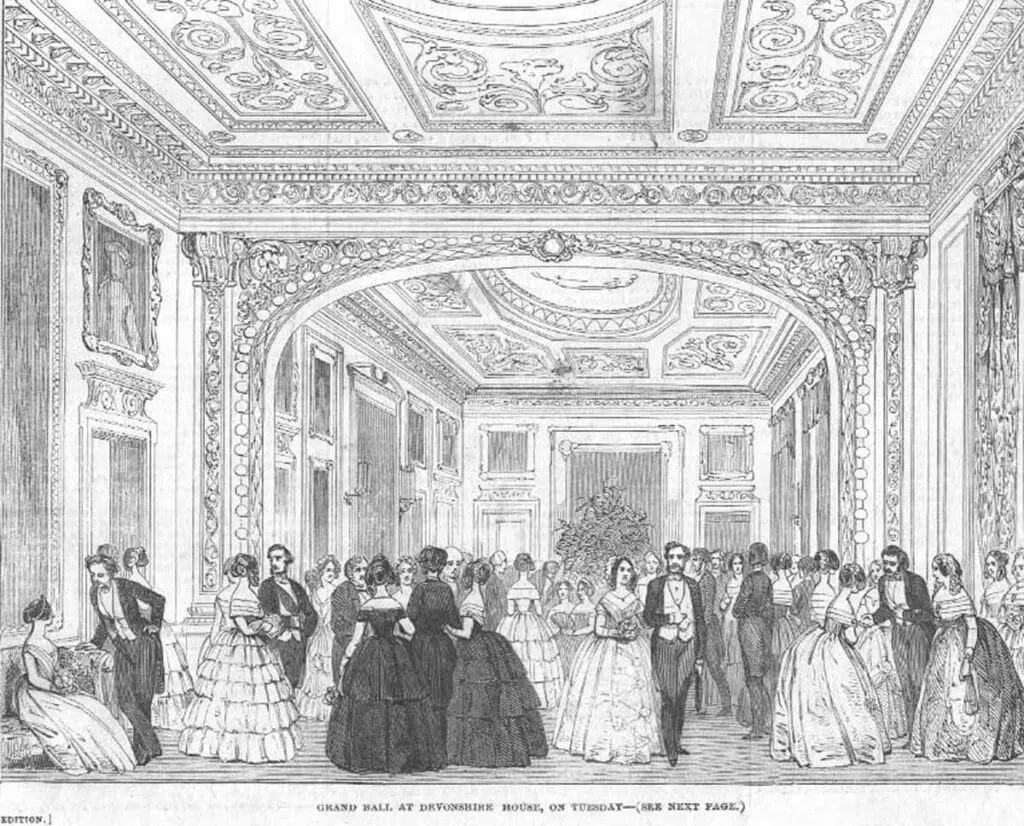

In a twist of fate, the fire occurred when London society was undergoing a shift in social events, with large gatherings consisting of dance, wine, and merriment becoming the norm.

The Duke of Devonshire saw this as an opportunity to rebuild Devonshire House in the form of a vast, majestic palace fit for hosting balls and concerts. The Duke commissioned William Kent to design the palace, Kent’s first for a London house.

He created a sprawling house over three storeys in eleven bays, in a design described as “severe” despite its Palladian style. The building of the palace took around six years and finished in 1740.

Indeed, the stark interior gave little hint as to the riches contained inside, with the Devonshire art collection, one of the finest in England in the 18th Century, housed within.

Oh, and a 40-foot-long library that, among other treasures, contained Claude Lorraine’s Liber Veritatis, the artist’s complete record of sketches.

Alterations and the Victorian Age

During the late 1700s, James Wyatt made alterations to the palace before Decimus Burton created a new portico, grand staircase, and opulent entrance hall for the 6th Duke of Devonshire in 1843.

By this point, Devonshire House was one of London’s prime social hotspots, with people flocking to see the “Crystal Staircase” in particular, formed of newel posts and a crystal glass bannister.

The 5th Duke, William Cavendish, was a Whig supporter of Charles James Fox and became the setting for the remarkable social and political life of Cavendish’s circle of noble and political friends.

Such was the grandiosity of the palace that it became an entertainment centre for social events rather than a place to live.

In 1897, the house hosted the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria with a lavish and exquisite fancy dress ball – the Devonshire House Ball of 1897.

All the guests, including the Prince and Princess of Wales, dressed as historical portraits. Many photos of the event became well-known fixtures in the late Victorian era history books.

World War I and Demolition

The British Red Cross used Devonshire House during World War I as a postal sorting office. Eventually, the famous aeronautical pioneer Gertrude Bacon took charge of the office as part of her service that saw her awarded the British War Medal.

At the end of the war, the 9th Duke of Devonshire suffered death duties above £500,000. In addition, he inherited the significant debts of the 7th Duke, prompting the sale of many of the family heirlooms.

Among the treasures sold were several books printed by William Caxton, 1st editions of Shakespeare, and eventually Devonshire House itself, along with its three acres of gardens.

The house fetched a whopping £750,000, and the purchasers, Shurmer Sibthorpe and Lawrence Harrison decided to demolish the building.

Virginia Woolf mentions the demolition when her famous Mrs. Clarissa Dalloway describes “Devonshire House without its gilt leopards” as she walks along Piccadilly. While renowned war poet Siegfried Sassoon describes the demolition in his “Monody on the Demolition of Devonshire House.”

Devonshire House Today

A new office block was built on the site in the mid-1920s, leading directly onto Piccadilly and taking its name from the house it replaced. The office became the UK headquarters of Citroen before becoming HQ of the War Damage Commission during World War II.

Parts of Devonshire House are still visible today, with some artworks and furniture installed at Chatsworth House. The famous iron entrance gates, the absence of which Mrs. Dalloway bemoans, now stand on the other side of Piccadilly to form one of the entrances to Green Park.

Meanwhile, the wine cellar of Devonshire House is now the ticket office of Green Park Underground station. Sadly, no bottles remain for travellers to enjoy!

Devonshire House, London: Practical Information

- What little of Devonshire House remains can be seen by visiting Green Park Underground station and enjoyed as you walk through the ticket hall and along the south side of Piccadilly to where the wrought-iron gates stand.

- The current Devonshire House remains across the road from the entrance of Green Park on Piccadilly and is still home to several offices and shops on the ground floor, including Timpson shoe repairs and an M&S.

Address: Piccadilly, SW1